Chariots rumble, horses whinny low,

Each soldier with bow and arrow, aglow.

Parents and wives follow to bid farewell,

Xianyang Bridge lost in a dusty swell.

They hold their clothes, stomp their feet, and cry,

Their wails ascending to the sky on high.

A passerby asked the soldiers, “What’s wrong?”

“Frequent drafts have gone on for far too long,”

they responded with a weary sigh.

A boy drafted at just fifteen to defend the north river,

At forty, he still serves on the west front, a farmer in shiver.

Upon his dispatch, the village elder wrapped his hair, all black,

He returned with gray hair, but still had to go back.

Blood spills like seas on the battlefield,

Emperor Wu’s thirst for territories still unslaked.

Haven’t you heard?

Two hundred states east of Hua Mountains lie,

Thousand villages buried in briers, abandoned and dry.

Though strong women plough the fields with care,

Crops grow haphazardly, with yields so rare.

The soldiers here are well-known fighters,

But treated like dogs and roosters, their struggles afoot.

Though you may ask, they dare not complain,

For fear of the consequences, so much to explain.

Like this winter, the relief for the West Gate troop unclear,

The governor’s taxes demand, no one knows how to steer.

Had we known a boy child could bring such pain,

We’d rather have given birth to a girl, and not in vain.

At least a girl can marry a neighbor close by,

Boys buried far away, like weeds, pass by.

Haven’t you seen, by the shore of the Green Sea,

Skeletons scattered since ancient times, for all to see.

New ghosts wail and old ghosts weep,

On a dismal rainy day, their sorrows so deep.

“March of the Troops and Chariots” is a true record of historical life.

During the Tianbao reign of Emperor Xuanzong of the Tang Dynasty, the imperial court frequently launched attacks on the ethnic minorities in the frontier. In the eighth year (749), Ge Shuhan was ordered to attack Tubo Shibao City (in today’s Qinghai Province).

The 2,000 soldiers on Longju Island (in Qinghai Lake) were also wiped out. Ten years (751) in April, Jiannan Jiedu envoy Xianyu Zhongtong was ordered to attack Nanzhao (the main jurisdiction is in present-day Yunnan Province), and the result was a big defeat. 60,000 soldiers died, and Zhongtong only escaped. Due to the huge loss of troops in these two wars, the imperial court recruited troops on a large scale. This incident is vividly recorded in “Zi Zhi Tong Jian Thirty-two Tang Ji”:

People have heard that there are many miasmas in Yunnan, and ninety-nine percent of soldiers died before the war, so they are not willing to apply for recruitment. Yang Guozhong (the prime minister at the time) sent the censor to arrest people in different ways, and sent him to the military station with flails… So the traveler was sad, and his parents and wives sent him off, and the crying was loud.

Such a heart-rending scene is also rare in history! The poem “March of the Troops and Chariots” was probably written when the poet saw such a scene or shortly thereafter.

But the poet captures this historical lens in his poems, just using it as a prelude to a social tragedy, and his main intention is to expose the cruel oppression of the people by the ruling class. Therefore, right after this prelude, the content of this tragedy is demonstrated layer by layer through the question and answer of “pedestrians”: “When you go, you are with your head wrapped, and when you return, your head is white and you are still guarding the border.” “The front yard bleeds into sea water” – this is the death of millions of soldiers on the battlefield; “the Han family has two hundred prefectures in Shandong, thousands of villages and thousands of villages are born” – this means that the country’s rural production is withering; “County Officials are in a hurry to demand rent, so where does the tax come from”—this means that the people can’t even maintain their livelihoods, and the imperial court is still pressing for rent and tax. It can be seen that the basic point of this artistic generalization method is to outline the real situation of society in a historical period before the Anshi Rebellion from point to surface, from phenomenon to essence. After reading this poem, we can not only see the deep suffering of a whole generation, but also touch the poet’s fiery heart that sympathizes with the people.

The meaning of this poem is more than that, more importantly, it shows the poet’s firm stand against the “open frontier” war. “Blood in the front court turned into sea water, and the Emperor Wu opened the border without any intention”, which shows that he realized that this kind of unjust war is the root of all suffering; he dared to put the responsibility for the war on the supreme ruler. What poets do not have. The poet’s position is consistent. In “Exiting the Fortress”, he once wrote: “The king is already rich in the land, and there is so much to open up.” “Killing is limited, and the country has its own border.” This is exactly where the people’s nature of Dushi’s poems lies.

車轔轔,馬蕭蕭,

行人弓箭各在腰。

耶娘妻子走相送,

塵埃不見咸陽橋。

牽衣頓足攔道哭,

哭聲直上干雲霄。

道旁過者問行人,

行人但云點行頻。

或從十五北防河,

便至四十西營田。

去時里正與裹頭,

歸來頭白還��邊。

邊庭流血成海水,

武皇開邊意未已。

君不聞,

漢家山東二百州,

千村萬落生荊杞。

縱有健婦把鋤犁,

禾生隴畝無東西。

況復秦兵耐苦戰,

被驅不異犬與雞。

長者雖有問,

役夫敢伸恨?

且如今年冬,

未休關西卒。

縣官急索租,

租稅從何出?

信知生男惡,

反是生女好。

生女猶得嫁比鄰,

生男埋沒隨百草。

君不見,青海頭,

古來白骨無人收。

新鬼煩怨舊鬼哭,

天陰雨濕聲啾啾。

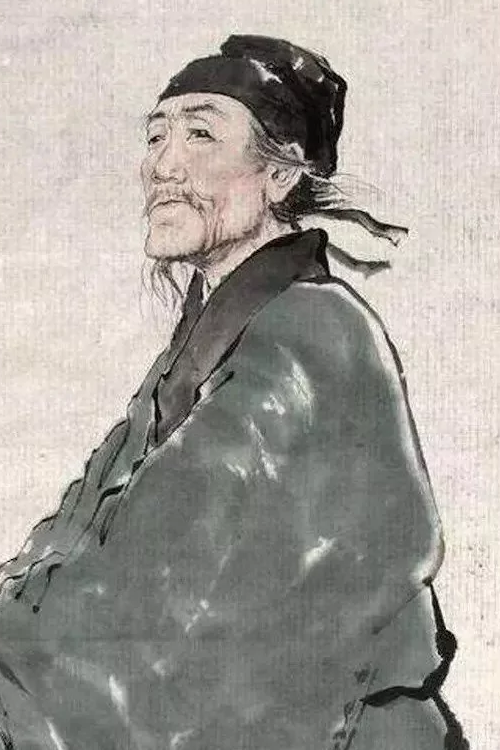

Du Fu (February 12, 712-770), courtesy name Zimei, nicknamed Shaoling Yelao, No. 1 Duling Yeke and Duling Buyi, was a realist poet in the Tang Dynasty. His works are famous for their grand social realism. The Du Fu family is a branch of the Jingzhao Du family. During the Tang Dynasty, the Jingzhao Du family called themselves Duling people. He used to be Zuo Shiyi and Wailang, a member of the Ministry of Inspection and Engineering, and later lived in seclusion in Chengdu Thatched Cottage, known as Du Suyi, Du Gongbu, Du Shaoling and Du Thatched Cottage in the world.

Image: MidJourney/DALL-E 2